How old were you when you realized your parents struggled with money?

I was five: crouched on the top stair, listening once again to my parents fighting downstairs. My mom wanted to know where all my dad’s money went each month. The math just wasn’t adding up. My dad, knowing his daughter was an eavesdropper, shouted for me to join them in the kitchen.

“Tell your mother I always provide for you,” he demanded.

I didn’t even understand the question at the time.

What I would come to understand by high school was that my dad, though light-hearted and charming, was a serial debtor. He’d go from business executive to blue-collar worker at age 65. My mom, though entrepreneurial and scrappy, struggled to find a focus. She’d go from one gig to the next, but few of them lasted.

By the time I was 24, my income surpassed both of my parents. It was clear, in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways, that they could use my help. I felt both grateful and bitter about providing it.

This dynamic flies in the face of Westernized portrayals of “healthy” parent-child relationships. But it’s not uncommon. In the United States alone, 1.4 million adults under 35 supported their parents in 2016.

If you’ve found your way here, you can probably relate, and are wondering where to begin.

Begin here. This article is dedicated to building the emotional awareness needed to make peace with this role-reversal. In part two of this series, we’ll get into tactical options for helping your parents based on your means and risk-tolerance.

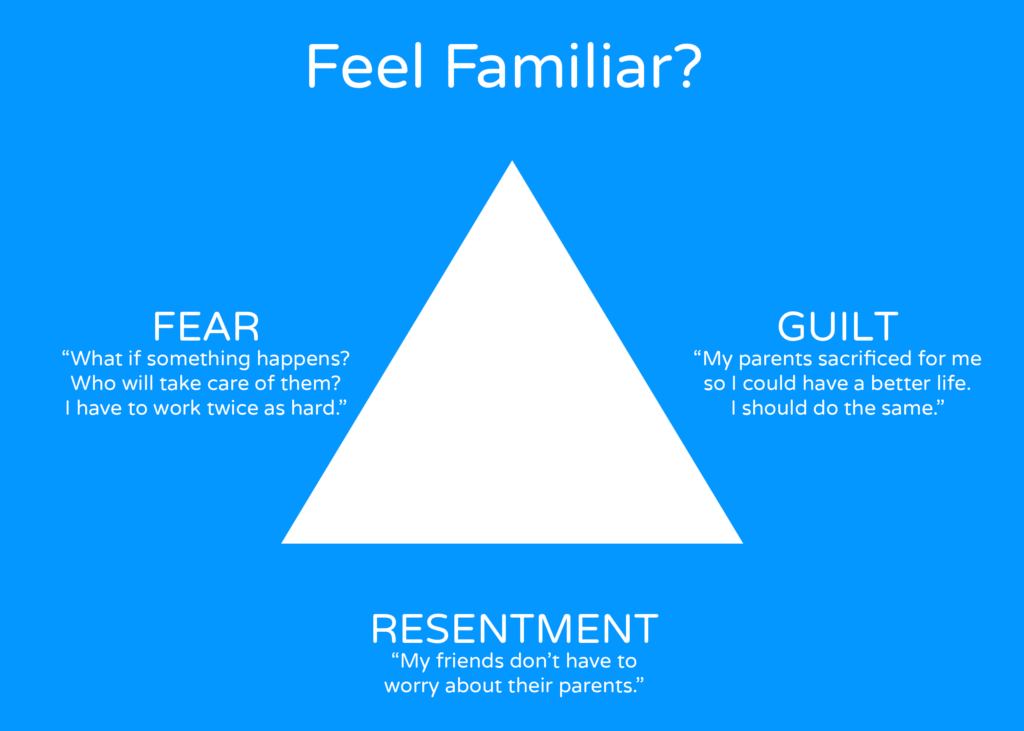

The Emotional Triangle

I’ve talked with dozens of adults who grew up with, or still coexist, with financially unstable parents. There’s three feelings that routinely come up in those conversations: fear, guilt, and resentment.

I mention these three not as criteria or “trauma benchmarks,” but to make a larger point: only when we can access, sit with, and name our feelings, can we begin to manage them. You may resonate with what I describe below and graft your own experience onto those words. You may choose to further explore your experience and select your own words.

Fear

My first chapter of financial security coincided with my parents’ divorce. My mom was forced out of a home she did not want to leave, but could not afford on her own. I feared for her well-being and safety.

When I look back, it’s clear that so many of my career ambitions were shaped by the fear that one day my parents would run out of means to care for themselves, and someone would have to step in.

Guilt

Up until my parents divorce, I had been shuttling my extra income towards settling my own debts, repairing my credit, and building a safety-net of my own.

But I had also seen the sacrifices my mom made for me over the years, often at the cost of her own needs and security. It only felt right to return the favor.

I put my own financial goals on pause and re-allocated funds to help my mom with the mortgage and groceries. No one wants to see a person they love struggle, especially when that person is the reason for your existence. But I also felt resentful.

Resentment

While many of my peers still relied on their parents to underwrite their leases and help with rent, I was calculating whether my income could qualify my mom for a comfortable apartment of her own.

I was jealous that my friends could spend their whole lives, and paychecks, on themselves, and not think twice about their parents’ security.

Some people, particularly those who grew up as the children of immigrants and were acquainted with the idea of sending money to their family, understood. Other people saw me helping my mom as a breach in the parenthood contract, and told me it was “deeply unfair.”

The reality is that life is unfair.

There will be times when life sits you down and reminds you that you are not entitled to the cards you want. You do, however, get to choose how you play your hand. So let’s talk about how to decide that.

Should you financially support your parents?

We’re tortured by this question because it asks us to weigh our own self-interest against our empathy for others. Like most questions in life, there is no right answer. The right answer is the one you can make peace with. Before you answer the big, hairy, “Should I help my parents?” question, I encourage you to answer two preliminary questions:

Can I afford to?

Your life is, first and foremost, your own. If you’re financially struggling yourself, covering your own bases must take priority.

I wouldn’t have been able to help my mom had I not first worked to settle my own debts, repair my credit score, and pick up short-term side gigs to build some savings.

It can feel selfish. It can be brutal to set that boundary. But you can do so with candor and kindness. It can be as straightforward as telling your parents: “I know you’re struggling right now. I want to help because I love you. But in order to help, I need to handle some things on my end first. Can we check in in X months?”

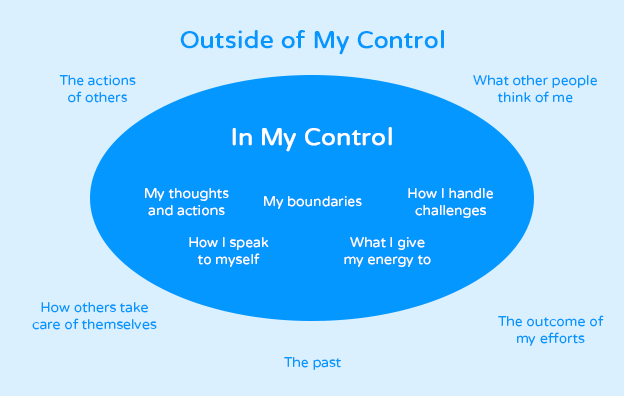

You can’t control how your parents react to this boundary. Some will be disappointed. Some will immediately understand and, with this new information, find other options. Either way, you’ve taken ownership of your own needs, and communicated them clearly.

As Prentis Hemphill once said, “Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” As you begin to internalize those words, this is also a helpful visual to hold onto:

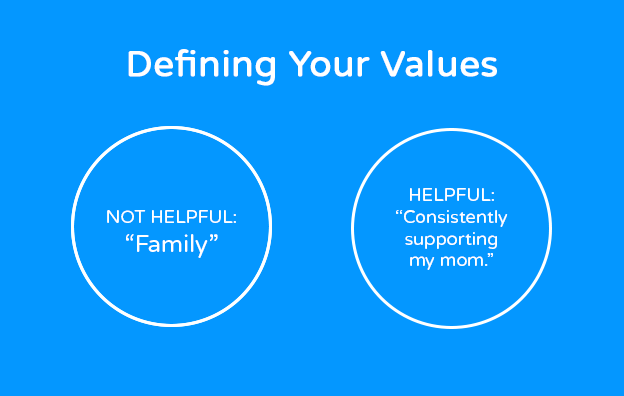

Does helping my parents align with my values?

A large source of our suffering comes from living with unclear values.

We may want to live one way, but make choices in service to something else: be it a higher priority or a desire to avoid discomfort.

I’ve learned through years of therapy that getting clear on your values, and their priority, provides a clear framework for our relationships.

I’ve also realized that the most useful values are phrased as verbs, not nouns.

“Family” is too broad of a value to offer any actionable guidance.

“Consistently supporting my mom,”(which is one of my refined values)provides clear direction for behavior, while still leaving flexibility for how I might fulfill it.

There’s been chapters in my life where supporting my mom looked like calling her every Sunday and letting her know I was thinking of her. At other times, it looked like sending her money for housing and food. The latter version was far more uncomfortable, but the discomfort of it was mitigated by my desire to embody my values.

In other words, getting clear on your values softens the edge of resentment.

You’ll likely have different values for different domains of your life. A value for your friendships may not make sense for your romantic relationships, or your relationship with your parents.

In an ideal world, you can fulfill your various values in tandem. But oftentimes, your personal values may conflict with your family values. If that’s the case, I encourage you to rank your values in order of priority, own that prioritization, or consider refining your values so that they can coexist and be fulfilled alongside each other.

Recommended Resources

Figuring this stuff out takes time and honesty. This book, particularly chapters 11-13, is a useful guide. If more support is necessary, I would encourage you to find an affordable therapist that specializes in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which builds on the value development framework I outline above.

Once you’ve taken the time to get honest with yourself about your own finances and values, you’ll be better equipped to help your parents. If, after reading this article, you feel ready and willing to offer financial support for your folks, check out part two of this series for strategic ways to help.

Leave a Reply